Stories 3 - Life with TS

Marcie’s Story

Sunday, September 10, 2000

The Flint Journal

ON THE BLINK… People with Tourette often have strange, misunderstood symptoms by Rose Mary Reiz, Journal Staff Writer

Tim and Barbara Hill’s oldest son seemed to have an attitude problem. He interrupted conversations by fidgeting and yelping. When entering a room, he jumped and swiped his hand across the ceiling. Sometimes, on his way to bed, he turned the thermostat all the way up or down.

“We thought he was just a kid being obnoxious,” said Hill, a Clio postal worker. “We kept telling him to stop it.”

His son would straighten up, but never for long, one evening, Dad’s patience ran out. “We were sitting at the dinner table, and he was making all these noises. I kept telling him to stop. When he didn’t, I just got infuriated.”

His son stared back at him with what looked like defiance and let out a high-pitched yelp. Without thinking, Hill took the back of his hand to him.

Ten years later, he still feels bad about it. “It’s called drastic guilt,” Hill said. “But when you don’t know what you’re dealing with, the frustration can be overwhelming.”

One evening, the Hills watched an episode of “L.A.Law” that featured a character who, because of a disorder called Tourette Syndrome, jerked and yelped uncontrollably. Tim and Barbara looked from the television screen to each other both wondering the same thing.

A trip to the family doctor confirmed their suspicions. The Hills’ oldest son, now an adult who prefers his name not be used, was diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome (TS).

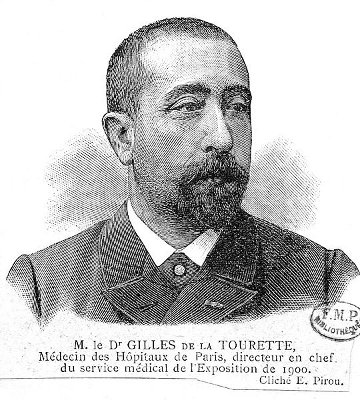

Named for the French neurologist who first described it, Tourette Syndrome is a neurological disorder characterized by involuntary vocal and motor tics. Symptoms include head jerking, eye blinking, facial grimacing, finger tapping, muscle flexing and shoulder shrugging. Vocal tics include barking grunting, humming, shrieking and throat clearing.

Tourette Syndrome is one of the most misunderstood disorders known to medicine. Many associate it with involuntary obscenities and thnic slurs, but fewer than 15 percent of those with TS have these symptoms. More common is the urge to repeat phrases or utter words out of context.

No one knows for sure what causes the disorder, which is thought to stem from abnormalities in the brain chemical, dopamine. An estimated one in 1000 people have the syndrome, which is inherited.

“Once we knew what to look for, we could trace some Tourette symptoms, like eye blinking, back through my wife’s family,” Hill said. “But unless the symptoms are severe, you’d just think they were funny habits someone had.”

Many people with TS never have been diagnosed, but it is known that more males than females are affected. Most begin experiencing symptoms as children. The tics wax and wane, sometimes disappearing for months at a time. Stress makes symptoms worse. Most people get better as they mature. As many as one-third are symptom-free by adulthood.

Changing symptoms make Tourette Syndrome tricky to diagnose. Because children can sometimes control the tics for short periods of time, parents and teachers often mistakenly assume that the actions are voluntary. “With a lot of effort, someone can stop the tics for a while,” Hill said. “But it only postpones more severe outbursts. Tics are irrepressible, like sneezed. Eventually they come out.”

Like most parents of kids with TS, the Hills were at first filled with anxiety and guilt. “You go through this stage where you keep wondering, ‘What did we do wrong? Who’s to blame for this? Why didn’t we figure it out?’” Hill said.

“After a while, you realize it doesn’t do any good to try to figure out the cause. You’ve got to deal with it and move on.”

Countless children with TS have been mistakenly labeled “bad kids” because parents and teachers view their behaviors as bids for attention.

One Grand Blanc mother, whose 18-year-old son has TS, struggled for years to make his teachers understand that he had behaviors he couldn’t control. “Some teachers were wonderful about working with him, but others labeled him a bad kid, and the label followed him throughout his school years. He spent a lot of time in the principal’s office.”

He was once kicked out of a classroom for tapping his pencil on the desk when the noise was actually coming from his tongue, which he couldn’t stop clicking.

Like most people with TS, the boy also suffered from Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder, which involves poor impulse control and problems focusing attention, and Obsessive Compulsive Disorder, which involves repetitive ritualistic behaviors.

“He had facial grimacing and eye blinking, but he also was diagnosed with mild ADHD,” the mother said. “He had compulsions, like needing to trace one letter or number over and over. It would take him forever to finish a test.”

Most students with TS don’t require special education. Many can succeed academically with the help of classroom modifications such as allowing more time or a special location for test-taking. Although there is no cure for TS, medication can sometimes help control tics and obsessions. The emotional impact of the disorder is often more disabling than physical symptoms.

“Our oldest son was embarrassed and didn’t want anyone to know he had Tourette’s,” Hill said. “He didn’t want to be labeled as weird. He’d rather a teacher think he was acting up than know the truth.”

Keeping such a secret takes an emotional toll and inhibits friendships. But the impulse to hide Tourette Syndrome is understandable. People often make fun of, or look down upon, those with symptoms.

Daniel T. Anbe, a cardiologist at McLaren Regional Medical Center, knows how rough people can be on Tourette patients. His son, Darryl, 34, has the disorder. “When Darryl was young and we’d go out in public, people would look at us like, ‘Can’t you discipline your kid?’ It was embarrassing for all of us.”

Darryl, who has severe head jerks and vocal outbursts, has sometimes been asked to leave theaters and restaurants. “As a family, we’re always walking the line between not having Darryl become reclusive, while recognizing that Tourett’s is distracting to other people,” Anbe said.

“We’ve found out that movies probably aren’t the best place for someone with Tourette’s. In restaurants, we explain to the waitress that we need a booth in a corner, and we seat Darryl so that he’s facing the wall. That way, if he jerks or yells, fewer people notice it.”

When boarding a plane, Darryl distributes cards explaining his condition to stewardesses and nearby passengers. “Most people are understanding once they know what the problem is,” Anbe said. “It’s the unknown that frightens people.”

The balance between a Tourette patient’s desire for a normal life and the public’s desire for peace was highlighted this year when a Hamtramck grocery store clerk with Tourette Syndrome sued Farmer Jack after he was fired for uttering vulgarities that offended customers. The case pitted the man’s right to work under the Americans with Disabilities Act against the employer’s right to hire someone who does not offend customers and employees.

The Michigan Court of Appeals recently ruled in favor of Farmer Jack, stating that in this case, the man’s condition renders him unable to perform in a job that requires contact with the public.

Only those with the most severe symptoms will experience such problems. Most Tourette patients lead normal lives. They populate and almost every profession including doctors, lawyers, and professional athletes.

The Grand Blanc boy who was once labeled a classroom troublemaker is now a college student studying computer science. The Hills oldest son is in his 20’s, employed and lives on his own. Few of his friends or co-workers even realize he has the disorder.

Anbe serves on the Tourette Syndrome Association’s national board of directors. He devotes much of his time to educating the public about and helping raise money to fight the disorder.

“We still don’t have the right treatment for Tourett’s, and we still haven’t identified the gene that causes, it,” Anbe said, “but hopefully we’re getting closer.”

Like Anbe, Tim Hill has armed himself with knowledge about the disorder and has devoted much of his time to educating others. He is past president of the Central Michigan Chapter of the Tourette Syndrome Association.

When their youngest son, Andrew, 14, was diagnosed with Tourette Syndrome, Tim and Barbara were ready to deal with the problem head-on. “This time, we knew what we were dealing with,” Hill said. “It didn’t seem like such a big deal.”

Andrew sometimes blinks, jerks his head and cracks his knuckles excessively. He is an outgoing honor student who is open about the disorder. “Sometimes kids make fun of me, but I just tell them I have Tourette’s. Then they usually just say, ‘Oh,’ and quit bothering me about it.”

The disorder is increasingly featured in books, educational videos and films that go beyond the stereotype of Tourette’s as a “swearing disease.” Across the country, support groups give families coping with TS an opportunity to share with others who understand. Flint-area families may attend support group in the Detroit and Port Huron areas.

“Sometimes people with Tourette’s are more comfortable in the support group than they are at home,” Hill said. “In the group, you can tic all you want and no one thinks anything of it.”

Like Andrew, most Tourette’s patients are willing to explain their disorder to those they come in contact with. They hope only tat others will attempt to understand.

“I guess what we’re looking for from the public,” Anbe said, “is acceptance and tolerance.”